This post was dictated over a few weeks using Wispr Flow and refined with AI tools for fact-checking, cross-referencing, and research. I frequently update what I write, so this may change from the original version without notice. For further details, see my AI policy.

What are we building?#

I’m going to walk through building a multi-framework GRC agent. Along the way we’ll cover:

- Analyzing SSPs (System Security Plans), policies, and AI system cards across security frameworks (NIST 800-53, CMMC, EU AI Act, and more)

- Cross-mapping controls across multiple standards

- Returning structured findings with practical POA&M (Plan of Action and Milestones) entries

- Wiring up CLI tools and MCP servers so the agent can actually read files, parse documents, and call APIs

- Delegating specialist work to subagents

- Converting compliance artifacts to OSCAL format (one approach to the machine-readable direction FedRAMP 20x is heading)

- Running interactive follow-up sessions after an assessment

We’ll go through the actual code for each piece and keep it simple without dumbing down the technical details. These are examples for you to think about, not fully fleshed out implementations.

Beyond that surface-level checklist above, what matters is how the agent reasons through those capabilities.

At assessment depth, it does not stop (and whatever you build should not stop) at “is AC-2 implemented?” which would just be reiterating the checkbox process all over again. It can evaluate enhancements like AC-2(1) through AC-2(5) against the selected baseline and evidence set. And it can take into consideration things that a more straightforward check-the-box exercise workflow would probably not do. I use FedRAMP/FISMA Moderate (pre FedRAMP 20x) as the running example here but you could apply this to any compliance framework really. Just use your imagination.

Why NIST and FedRAMP? NIST 800-53, FedRAMP baselines, and FIPS publications are public domain under 17 U.S.C. § 105: federal government works carry no copyright restrictions on control text. That’s why this demo can include real control language and ship as an open-source repo. Proprietary frameworks like PCI DSS, SOC 2, and ISO 27001 have restricted control text that would make an open-source demo legally complicated. The agent patterns themselves are framework-agnostic, so swap in your own framework data and the same architecture applies.

It also uses FIPS 199 categorization and shared responsibility models to figure out which controls actually apply to your environment. The same control text can mean different things depending on your boundary and who owns what. Cross-mapping evidence across multiple frameworks is where a lot of orgs get stuck, and it’s exactly the kind of tedious work an agent can help with. How many times have you been charged with creating an internal common controls framework at this point?

The agent reasons across SSPs, policies, and system evidence rather than treating each document in isolation. For AI systems, it extends into EU AI Act risk-tier classification and NIST AI RMF maturity assessment. And yes, I know this is like some inception shit because you have an AI evaluating an AI framework.

Leveraging Deterministic and Non-Deterministic Behaviors of AI Agents#

There is a lot of discourse about how AI workflows are non-deterministic, but non-determinism is often the point. I regularly use an LLM to check myself: “What am I missing?” That exploratory reasoning surfaces blind spots that a scripted workflow wouldn’t. For repeatable checks where you need consistent output, just write a deterministic tool. Write some code. The trick, I think, is having both in the same system.

Rigid branching breaks on messy evidence. Real-world artifacts are often inconsistent, references are missing, and implementation details are spread across documents. A hardcoded workflow follows paths you predicted. An agent investigates what is actually there and adapts its next step. If an upstream API changes and breaks a script, a rigid workflow stalls. An agent with bounded tools can inspect the failure, adjust its path, and continue under human review.

If you work in GRC, you already know the pain: validating hundreds (probably thousands) of controls, reviewing hundreds of pages of documentation, wrangling evidence spreadsheets that multiply overnight, and chasing policy documents that always seem to be one revision behind. What AI workflows are revealing is that much of this data could be far more structured, but right now most orgs are all over the place.

Will AI Agents Fix Everything? Do you even need an AI Agent?#

Also to be clear, I’m not claiming an AI agent fixes all of GRC, but used carefully it can remove a lot of repetitive overhead and even improve tasks typically “automated” by code.

This leads to another point. Using an LLM or coding agent makes generating code so easy that you can take a completely different direction: develop fully deterministic workflows and adapt them just as fast. What used to take a month of scripting now takes days or hours. You end up with two powers in the same toolkit: the agent’s non-deterministic reasoning for exploratory analysis, and rapid generation of deterministic automation for repeatable checks. This, however, does require that you understand some basic coding fundamentals. I’ll cover that workflow in a future post maybe.

That’s largely been my approach since around 2018: using LLMs as an extension of work I was already doing, not trying to get an AI agent to do everything for me.

Let’s Get to Work Now#

Everything below assumes terminal comfort and basic scripting. If your team prefers something lower-code, tools like n8n, Langflow, and other agent builders can achieve similar patterns. My goal here is to help people understand how these agents work on a more fundamental level so they can make the best decisions for themselves and their teams.

Most GRC analysts live in Word docs, PDFs, and Excel sheets, not terminals. What if you gave an AI agent the tools an engineer actually reaches for (terminal access, file system access, spreadsheet parsing, PDF reading, scripts, API access) and pointed it at those same compliance problems?

This is a proof-of-concept demo, not a production system. If you ship something like this for real you’ll need to do more engineering, more threat modeling, and more red teaming first.

Assessment outputs are model-generated and should always be reviewed by qualified personnel in a human-in-the-loop process. For high-assurance government decisions, add formal oversight and hardening aligned with whatever compliance regime you fall under. This space is still relatively new but the NIST AI RMF governance and implementation guidance might be a good place to start.12

Let’s start with a working run first, then unpack why the SDK architecture matters and how the tool wiring works.

Building the GRC agent#

export ANTHROPIC_API_KEY=your-key-here

# or: claude auth login (if you have Claude Code CLI)

git clone https://github.com/ethanolivertroy/claude-grc-agent-demo.git

cd claude-grc-agent-demo

npm install # builds automatically via prepare script

npm link # makes grc-agent available globally

grc-agent --framework "NIST 800-53" --baseline "FedRAMP Moderate" \

--scope "demo" examples/sample-ssp.mdexport ANTHROPIC_API_KEY=your-key-here

pip install claude-agent-sdk anyio

git clone https://github.com/ethanolivertroy/claude-grc-agent-demo.git

cd claude-grc-agent-demo/python

pip install -e . # installs grc-agent CLI entry point

grc-agent --framework "NIST 800-53" --baseline "FedRAMP Moderate" \

--scope "demo" ../examples/sample-ssp.mdThe #!/usr/bin/env node shebang at the top of src/agent.ts survives compilation. TypeScript added shebang pass-through support in the TypeScript 1.6 milestone, so tsc preserves a first-line #! for CLI workflows.3 That means the compiled dist/agent.js is directly executable by the OS without a wrapper script, which is why npm link can wire it up as grc-agent with nothing else in between. In plain terms: you write TypeScript, compile it, and the result is a CLI command you can run directly from your terminal.

Why Use an SDK?#

You can run this process ad hoc in Claude Code each time. Building a custom agent gives you more repeatability: fixed tools, fixed output schemas, and less prompt overhead every run. Cost-wise, you save on tokens per run, which adds up fast if you build many LLM-based tools.

If you’ve ever built agent loops directly against the raw API, you’ve probably wired up something like this:

- Call the model

- Check if it requested a tool

- Execute the tool

- Append the result back into the conversation

- Repeat the loop

The SDK removes all of that manual orchestration. Instead, it provides a managed agent loop with:

- Streaming responses out of the box

- Built-in file/system tools: Read, Write, Edit, Bash, Glob, Grep

- Structured outputs validated against a JSON Schema

- Sub-agents that the main agent can delegate tasks to

- Custom tools via MCP servers

- Sandbox isolation with configurable permissions

Frameworks handle the edge cases that are tedious to get right by hand (streaming, retries, schema validation, sandboxing) so you can spend your time on domain logic instead of plumbing. And when improvements land upstream, you get them for free instead of adding them to your own backlog.

With that motivation, here’s what the simplest agent looks like.

SDK basics: your first agent#

Now that you’ve seen a full GRC run, let’s isolate the simplest possible SDK loop. If you want a deeper tutorial on the SDK itself, Nader Dabit wrote an excellent walkthrough.4

Here’s a minimal agent that lists files:

import { query } from "@anthropic-ai/claude-agent-sdk";

async function main() {

for await (const message of query({

prompt: "What files are in this directory?",

options: {

model: "claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929",

allowedTools: ["Glob", "Read"],

maxTurns: 10,

},

})) {

if (message.type === "assistant") {

for (const block of message.message.content) {

if ("text" in block) console.log(block.text);

}

}

}

}

main();import asyncio

from claude_agent_sdk import query, ClaudeAgentOptions

async def main():

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

model="claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929",

allowed_tools=["Glob", "Read"],

max_turns=10,

)

async for message in query(

prompt="What files are in this directory?",

options=options,

):

if message.type == "assistant":

for block in message.content:

if hasattr(block, "text"):

print(block.text)

asyncio.run(main())That’s it. Claude will use Glob to find files, Read to examine them if needed, and tell you what it found. The query() function returns an async generator that streams messages as Claude works.

Adding structured output#

For programmatic use, enforce a JSON schema:

const schema = {

type: "object",

properties: {

files: { type: "array", items: { type: "string" } },

summary: { type: "string" },

},

required: ["files", "summary"],

};

for await (const message of query({

prompt: "List all TypeScript files",

options: {

model: "claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929",

allowedTools: ["Glob"],

maxTurns: 10,

outputFormat: { type: "json_schema", schema },

},

})) {

if (message.type === "result" && message.subtype === "success") {

const result = message.structured_output as { files: string[]; summary: string };

console.log(result.files);

}

}schema = {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"files": {"type": "array", "items": {"type": "string"}},

"summary": {"type": "string"},

},

"required": ["files", "summary"],

}

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

model="claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929",

allowed_tools=["Glob"],

max_turns=10,

output_format={"type": "json_schema", "schema": schema},

)

async for message in query(prompt="List all TypeScript files", options=options):

if message.type == "result" and message.subtype == "success":

result = message.structured_output

print(result["files"])The SDK validates Claude’s response against the schema and retries if it doesn’t conform. You always get valid, typed JSON back. We’ll cover the full assessment schema in Structured output: making findings machine-readable.

That’s the foundation. Now let’s look at capability wiring decisions (Bash, CLI, and MCP).

The Stack#

The agent ships in two languages, TypeScript and Python, both using the Claude Agent SDK:

| TypeScript | Python | |

|---|---|---|

| SDK | @anthropic-ai/claude-agent-sdk | claude-agent-sdk |

| Runtime | Node.js (ES2022 / NodeNext) | Python 3.10+ / anyio |

| Schema validation | Zod | JSON Schema dict |

| Model | claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929 (configurable via CLAUDE_MODEL) | claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929 (configurable via CLAUDE_MODEL) |

Both versions share the same data/ directory of framework JSON files and produce identical structured output. The code examples below show both languages side by side.

Bash vs Tools vs Codegen#

The SDK gives you three ways for agents to take action. Knowing when to use each matters:

Tools are for atomic, irreversible operations: API calls, database writes, sending emails. Fixed interface, one thing per tool. Trade-off: 50 tools = 50 schemas in context.

Bash is the workhorse: composable, flexible, minimal context cost. wc -l, grep -r "AC-2", jq '.findings | length', pipe them together. Thariq Shihipar calls this “bash is all you need”,5 and for most agent work, he’s right. Bash handles the long tail of operations that don’t justify a dedicated tool. The flip side: a shell is typically all a hacker needs too, so giving an agent unsandboxed bash access is giving it the same attack surface. Sandbox it, scope its permissions, and treat it like you would any privileged service account.

Codegen is for dynamic logic where the operation itself needs to be computed. The agent writes a script, executes it, uses the result. Heavier than bash; use when piping commands together becomes unwieldy.

For this GRC agent, the split is: MCP tools for domain-specific operations (control lookup, gap analysis, POA&M generation), Bash for file operations and verification, and no codegen since the domain logic is predictable enough to encode in tools. That said, code execution is easy to add if your use case calls for it.

The token tax: CLI vs MCP#

The three-mode framework helps you think about what kind of action the agent takes. But the decision you’ll actually revisit on every tool is more specific: should this capability be a CLI tool called via Bash, or a structured MCP server? Remember, 50 tools means 50 schemas injected into context. That has a cost.

The numbers#

Microsoft’s Playwright team notes that CLI workflows are more token-efficient than MCP because they avoid “loading large tool schemas and verbose accessibility trees into the model context.”6 The Playwright team’s own benchmarks put numbers to this: ~114K tokens for the MCP approach vs ~27K for the CLI, 76% fewer tokens for the same browser automation task.78 The exact savings are task-dependent (simpler tasks show a smaller gap910), but the structural advantage holds: CLIs don’t inject schemas into context.

The baseline overhead adds up fast. A modest 5-server MCP setup consumes ~55K tokens before the conversation starts, just tool schemas sitting in context.11 And MCP results are unpredictable: a take_snapshot() call can return anywhere from 5K to 52K tokens depending on page complexity.10 CLI output is bounded by the command you run. Even Playwright’s MCP server doesn’t expose all available tools by default. Features like PDF generation and tracing are opt-in because their schemas consume too much context.9 The CLI has no such limitation since it doesn’t inject schemas at all.

Decision table#

| CLI via Bash | MCP server | |

|---|---|---|

| Context cost | Near zero (command + output) | Schema injected per server; 5 servers ≈ 55K tokens |

| Output predictability | Bounded, you control the command | Variable, 5K–52K for the same call |

| Integration effort | Zero, if it has a CLI, it works | Build or configure an MCP server |

| Structured I/O | Parse stdout yourself | Typed params and JSON responses |

| Best for | Existing CLIs, simple queries, file ops | Domain operations needing rich schemas |

The mitigation: deferred tool loading#

Claude addresses MCP bloat with Tool Search (deferred loading). Instead of injecting every tool schema at conversation start, schemas load on demand when the agent actually needs them. Anthropic’s benchmarks measured an 85% reduction in token usage with this approach.11 For a GRC agent wiring up multiple MCP servers (compliance lookups, vulnerability databases, evidence stores), deferred loading keeps the context budget from being consumed by schemas the agent never calls in a given session.

The rule of thumb#

Start with Bash. If the tool has a CLI and parseable output, you’re done. Most compliance tools fit here. An added benefit: any bash script you write for the agent is also a script a human can run, so your agent’s verification steps double as repeatable end-to-end checks your team can execute without the agent.

Graduate to MCP when structured schemas help the model reason about complex inputs, or when typed JSON output matters more than context efficiency, think multi-step workflows where the model needs to understand parameter relationships. MCP also shines with structured data formats (JSON, XML, OSCAL) where the model benefits from knowing the exact shape of both the request and the response rather than parsing raw stdout through jq or xmllint. MCP also wins when portability matters. If your agentic loop needs to run across environments (browser, desktop, mobile), MCP’s standard protocol works everywhere a JavaScript runtime does.

Use deferred loading when MCP is justified but the tool count is high. Let the agent pull schemas as needed rather than paying the full tax upfront.

With that cost model in mind, here are the tools wired into this GRC agent, and why each one landed where it did.

Wiring up CLI tools#

If you work in GRC, you’ve probably accumulated scripts and utilities, things you built to solve specific pain points. Those aren’t throwaway tools. Any CLI you’ve built is already an agent capability: if it runs in a terminal, the agent can run it too. Most already support --format json or play nice with jq. You don’t need to rewrite anything.

I built a lot of CLIs/TUIs last year (some public, some private), deliberately. CLIs make perfectly scoped tools for agent workflows. Here are three Go-based CLI tools I built for compliance work, each solving a specific problem:

- fedramp-tui: Browse FedRAMP documentation, search requirements across all 12 document categories, and look up Key Security Indicator (KSI) themes mapped to SP 800-53 controls. During an assessment, the agent can query FedRAMP requirements directly instead of relying on static data files alone. You could paste the entire FedRAMP machine-readable JSON into the agent’s context, but the NIST 800-53 catalog alone is 100K+ tokens. That’s a huge chunk of your context window burned on every API call, even when the agent only needs one control. A tool like this lets the agent query just AC-2 and get back exactly what it needs, keeping the context lean and the responses precise.

- cmvp-tui: Search NIST’s Cryptographic Module Validation Program database. When assessing SC-13 (Cryptographic Protection), the agent can verify whether a system’s cryptographic modules hold valid FIPS 140 certificates, a requirement that’s tedious to check manually across dozens of modules.

- kevs-tui: Search CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog with EPSS (Exploit Prediction Scoring System) scores. For RA-5 (Vulnerability Scanning) and SI-5 (Security Alerts), the agent can check whether discovered vulnerabilities appear in the KEV catalog and prioritize remediation by exploit probability.

Each tool has a CLI interface, so the agent uses them the same way you would:

# Search FedRAMP requirements by document category

fedramp-tui search "continuous monitoring"

# Check if a cryptographic module is FIPS 140 validated

cmvp "OpenSSL"

# Look up whether a CVE is in the CISA KEV catalog

kevs-tui agent "Is CVE-2024-3094 in the KEV catalog? What's the EPSS score?"From CLI to MCP: structured tool access#

Bash works for most things, but sometimes you want structured input and output: typed parameters, JSON responses, tool schemas the model can reason about. That’s where MCP comes in.

fedramp-docs-mcp indexes FedRAMP’s Machine-Readable (FRMR) datasets and 62+ pages of markdown documentation, exposing them as 21 structured tools across six categories: document discovery (list_frmr_documents, list_versions), KSI analysis (list_ksi, get_ksi, get_theme_summary), control mapping (list_controls, analyze_control_coverage), search and lookup (search_markdown, search_definitions), analysis (diff_frmr, get_significant_change_guidance), and system utilities (search_tools, health_check).

Adding it to the agent is one config entry in the mcpServers dict:

mcpServers: {

"grc-tools": grcMcpServer,

"fedramp-docs": {

command: "npx",

args: ["fedramp-docs-mcp"],

},

},mcp_servers={

"grc-tools": grc_mcp_server,

"fedramp-docs": {

"command": "npx",

"args": ["fedramp-docs-mcp"],

},

},Now the agent has typed access to FedRAMP requirements, KSI mappings, and control coverage analysis, no Bash parsing needed.

This illustrates the two-path pattern for giving agents capabilities:

- Bash for tools that already exist as CLIs, zero integration work, install and go

- MCP when you want structured schemas, typed parameters, and richer tool descriptions the model can reason about

The same pattern applies to the bash scripts in this repo’s scripts/ directory, compliance metrics, evidence search, POA&M validation. None of these required MCP definitions; the agent calls them directly.

The point isn’t that you need these specific tools. It’s that the tools you’ve already built for your compliance workflow are agent-ready.

And if you haven’t built any yet, start by asking yourself what data you need, what APIs you already have access to, and what manual steps you repeat every audit cycle.

Custom tools: teaching the agent GRC logic#

A design principle runs through all our tools: lightweight heuristic + LLM reasoning. Each tool:

- Gives the agent a structured classification or data point

- The agent then reasons about why a finding matters, what the regulatory implications are, and what obligations follow

You get the best of both: structured data the schema can enforce, and nuanced analysis from the model.

GRC workflows are tool-heavy: control lookup, cross-framework mapping, evidence validation, POA&M generation. The SDK makes custom tools simple with its MCP integration.

Registering tools#

In TypeScript, we use createSdkMcpServer and the tool() helper with Zod schemas. In Python, the SDK provides a @tool decorator with JSON Schema dicts:

import { createSdkMcpServer, tool } from "@anthropic-ai/claude-agent-sdk";

import { z } from "zod";

export const grcMcpServer = createSdkMcpServer({

name: "grc-tools",

version: "0.1.0",

tools: [

tool(

"baseline_selector",

"Recommend FedRAMP baseline and DoD IL using FIPS 199 high-water mark.",

{ confidentiality_impact: z.enum(["low", "moderate", "high"]),

integrity_impact: z.enum(["low", "moderate", "high"]),

availability_impact: z.enum(["low", "moderate", "high"]),

data_types: z.array(z.string()), mission: z.string() },

async (args) => ({

content: [{ type: "text", text: JSON.stringify(await baselineSelector(args), null, 2) }],

})

),

// ... 9 more tools (gap_analyzer, finding_generator, ai_risk_classifier, etc.)

],

});from claude_agent_sdk import create_sdk_mcp_server, tool

@tool(

"baseline_selector",

"Recommend FedRAMP baseline and DoD IL using FIPS 199 high-water mark.",

{

"confidentiality_impact": {"type": "string", "enum": ["low", "moderate", "high"]},

"integrity_impact": {"type": "string", "enum": ["low", "moderate", "high"]},

"availability_impact": {"type": "string", "enum": ["low", "moderate", "high"]},

"data_types": {"type": "array", "items": {"type": "string"}},

"mission": {"type": "string"},

},

)

async def baseline_selector_tool(args: dict) -> dict:

return {"content": [{"type": "text", "text": json.dumps(await baseline_selector(args), indent=2)}]}

# ... 9 more tools

grc_mcp_server = create_sdk_mcp_server(name="grc-tools", tools=[baseline_selector_tool, ...])The tools are then exposed to Claude as mcp__grc-tools__<tool-name>. Let’s look at the implementations that matter most.

FIPS 199 baseline selection#

In federal compliance, baseline selection isn’t “pick a level.” It’s a formal FIPS 199 categorization where the highest impact across confidentiality, integrity, and availability determines the overall system categorization. Here’s the actual implementation:

export async function baselineSelector(request: BaselineSelectorRequest) {

const impactRank = { low: 1, moderate: 2, high: 3 };

// FIPS 199 high-water mark: overall impact = max(C, I, A)

const overallRank = Math.max(

impactRank[request.confidentiality_impact],

impactRank[request.integrity_impact],

impactRank[request.availability_impact],

);

// Map to FedRAMP baseline, then determine DoD Impact Level

const fedrampBaseline = ["FedRAMP Low", "FedRAMP Moderate", "FedRAMP High"][overallRank - 1];

const dodIL = classifyDoDImpactLevel(request.data_types, request.mission, overallRank);

return { fedramp_baseline: fedrampBaseline, dod_impact_level: dodIL, fips_199_categorization, rationale };

}This extends beyond FedRAMP into DoD Impact Levels:

- IL2: public and non-critical mission data

- IL4: CUI (Controlled Unclassified Information)

- IL5: higher-sensitivity CUI and mission-critical NSS data

- IL6: classified (up to SECRET)

IL5 and IL6 require DISA Cloud Computing SRG overlays on top of FedRAMP controls, the tool notes this in its rationale.

POA&M generation with risk-based timelines#

The findingGenerator tool creates POA&M entries with remediation timelines scaled to risk severity:

export async function findingGenerator(request: FindingGeneratorRequest) {

const now = new Date();

const risk = request.risk_level ?? "moderate";

// Remediation timeline scaled to risk severity

const remediationDays =

risk === "critical" ? 30 :

risk === "high" ? 90 :

risk === "moderate" ? 180 : 365;

const completionDate = addDays(now, remediationDays);

const midpointDate = addDays(now, remediationDays / 2);

return {

poam_entry: {

weakness_description: request.gap_summary,

scheduled_completion_date: completionDate,

milestones: [

{ description: "Develop remediation plan", due_date: midpointDate },

{ description: "Implement and validate", due_date: completionDate },

],

source: "assessment", status: "open",

// ... remaining POA&M fields (deviation_request, vendor_dependency, etc.)

},

};

}AI risk classification#

The aiRiskClassifier uses keyword-based heuristics to determine the EU AI Act risk tier. This is intentionally simple, it’s a first-pass classifier. The LLM does the nuanced reasoning about why a system is high-risk; the tool provides structured classification that feeds into the schema:

export async function aiRiskClassifier(

request: AiRiskClassifierRequest

): Promise<AiRiskClassifierResponse> {

const text = normalize(request.system_description);

if (text.includes("social scoring") || text.includes("subliminal")) {

return { eu_ai_act_risk_tier: "unacceptable", nist_ai_rmf_function: "govern" };

}

if (

text.includes("biometric") ||

text.includes("critical infrastructure") ||

text.includes("employment") ||

text.includes("law enforcement")

) {

return { eu_ai_act_risk_tier: "high", nist_ai_rmf_function: "map" };

}

if (text.includes("chatbot") || text.includes("recommendation")) {

return { eu_ai_act_risk_tier: "limited", nist_ai_rmf_function: "measure" };

}

return { eu_ai_act_risk_tier: "minimal", nist_ai_rmf_function: "manage" };

}The aiRiskClassifier is the clearest example of that tool-provides-structure, agent-provides-reasoning split: the tool returns the tier, and the agent explains why a biometric system in critical infrastructure triggers high-risk, what the specific Article 6/Annex III implications are, and what obligations follow.

At IBM Tech Exchange, I met JJ Asghar and he showed me a project he was working on called AI Abstract Classifier: it uses an LLM to score conference abstracts for AI-generated or sales-y language. We talked briefly about applying something similar to GRC: feed it policy documents or evidence artifacts and get back a score on how well they actually satisfy a requirement, not just whether the right keywords are present. It’s on my never-ending to-do list, but if you’re interested in that direction, the project is worth a look.

Tools as data providers#

The naive alternative (substring matching, token-presence checks) falls apart fast in GRC contexts, where the same requirement can be satisfied by implementations that share zero keywords with the control text. Two tools illustrate how the “tools as data providers, not decision-makers” pattern plays out in real assessments.

gap_analyzer takes a control ID and an implementation description, then returns:

{

control_id: "AC-2",

requirements: [ // full requirement text

"Define and document types of accounts allowed and prohibited",

"Assign account managers",

"Require approval for account creation requests",

// …

],

implementation_description: "Role-based access is enforced via SSO integration…",

heuristic_gaps: [ // hint: requirements whose keywords

"Assign account managers", // don't appear in the description

"Require approval for account creation requests",

],

}The heuristic_gaps array is a useful starting point, but it’s just a substring filter. An implementation that says “role-based access is enforced via SSO integration” genuinely does cover parts of AC-2, even though it doesn’t contain the literal text “assign account managers.” The agent gets the full requirements list and the implementation description together, so it can judge whether SSO-provisioned roles satisfy the account-manager requirement in practice. The heuristic narrows the search; the model makes the call.

evidence_validator follows the same shape. It takes a control ID and a list of file paths, reads each file, and returns:

{

control_id: "AC-2",

file_results: [

{

path: "/evidence/access-control-policy.pdf",

readable: true,

excerpt: "This policy establishes procedures for provisioning, reviewing, and deprovisioning…",

heuristic_match: false, // "ac-2" doesn't appear literally in the document

},

],

}An “Access Control Policy” document is perfectly valid AC-2 evidence, but heuristic_match is false because the literal token “ac-2” never appears in the text. That’s fine. The agent reads the excerpt, sees that the policy covers account provisioning and review, and determines relevance semantically. The heuristic flag helps prioritize which files to examine closely; the model decides what actually constitutes sufficient evidence.

This pattern also makes tools composable: any subagent can use the same data differently depending on its role. The control-assessor uses gap_analyzer output to write determination statements, the evidence-reviewer uses evidence_validator output to judge artifact sufficiency, and the gap-reporter aggregates both to produce a prioritized remediation list, all from the same underlying data, with different reasoning applied on top. The next section shows where these tools are orchestrated in the agent loop.

The agent loop: orchestrating an assessment#

The core of the agent lives in src/grc-agent.ts (TypeScript) or grc_agent/grc_agent.py (Python). The runGrcAgent() function:

- Loads evidence files

- Builds a framework-specific prompt

- Wires up the MCP server and subagents

- Streams the assessment with schema-validated output

export async function runGrcAgent(input: GrcAgentInput) {

// ... load evidence, build prompt, wire up subagents

for await (const message of query({

prompt,

options: {

model,

allowedTools: ["Bash", "Read", "Glob", "Grep", "Task", "TaskOutput", ...grcToolNames],

permissionMode: "bypassPermissions",

maxTurns: 50,

outputFormat: { type: "json_schema", schema: grcAssessmentSchema },

mcpServers: { "grc-tools": grcMcpServer },

agents,

},

})) {

if (message.type === "result" && message.subtype === "success") {

assessment = message.structured_output as GrcAssessment;

}

}

return assessment ?? fallbackAssessment(input, now);

}async def run_grc_agent(inp: GrcAgentInput) -> GrcAssessment:

# ... load evidence, build prompt, wire up subagents

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

model=model,

allowed_tools=["Bash", "Read", "Glob", "Grep", "Task", "TaskOutput", *grc_tool_names],

permission_mode="bypassPermissions",

max_turns=50,

output_format={"type": "json_schema", "schema": grc_assessment_schema},

mcp_servers={"grc-tools": grc_mcp_server},

agents=agents,

)

client = ClaudeSDKClient(options=options)

await client.connect(prompt=prompt)

async for message in client.receive_messages():

if isinstance(message, ResultMessage) and message.subtype == "success":

assessment = message.structured_output

await client.disconnect()

return assessment or fallback_assessment(inp, now)

A few things to notice:

permissionMode: "bypassPermissions": the agent runs headless, no interactive approval prompts. Essential for automated assessment pipelines. In a production or regulated environment, you’d scopeallowedToolstightly to read-only operations and run the agent within a sandboxed CI/CD pipeline with least-privilege credentials.outputFormatwithjson_schema, every response is validated against our schema and retried if non-conforming, as described above.mcpServers: our custom GRC tools are registered as an MCP server, making them available alongside the SDK’s built-in tools.agents: subagent definitions that Claude can delegate to via the Task tool.

The prompt itself is constructed from evidence excerpts:

function buildPrompt(input: GrcAgentInput, evidence: EvidenceSummary[]) {

return [

"You are a multi-framework GRC agent.",

`Framework: ${input.framework}`,

`Baseline/Level: ${input.baselineOrLevel}`,

`Scope: ${input.scope}`,

"",

"Analyze the evidence and produce a structured GRC assessment.",

"Use MCP tools for control lookup, mapping, gaps, and findings where helpful.",

"Return only valid JSON that matches the provided schema.",

"",

"Evidence excerpts:",

formatEvidenceBlock(evidence),

].join("\n");

}def build_prompt(inp: GrcAgentInput, evidence: list[EvidenceSummary]) -> str:

return "\n".join([

"You are a multi-framework GRC agent.",

f"Framework: {inp['framework']}",

f"Baseline/Level: {inp['baseline_or_level']}",

f"Scope: {inp['scope']}",

"",

"Analyze the evidence and produce a structured GRC assessment.",

"Use MCP tools for control lookup, mapping, gaps, and findings where helpful.",

"Return only valid JSON that matches the provided schema.",

"",

"Evidence excerpts:",

format_evidence_block(evidence),

])The prompt is intentionally minimal. Claude has access to Read/Glob/Grep to pull full file contents if the excerpts aren’t enough, and the MCP tools provide structured GRC data. The LLM does the actual assessment reasoning; we just give it the right tools and context.

Everything here goes into the prompt parameter (the user message), not a system prompt. The SDK supports a systemPrompt option ({ preset: "claude_code" } to inherit Claude Code’s full system prompt, or a custom string for your own). In production you’d likely separate role and behavioral instructions into the system prompt and keep only the task-specific content (framework, evidence) in the user message. For this demo, a single prompt works fine.

Structured output: making findings machine-readable#

Compliance findings are only useful if downstream systems can consume them. An SSP narrative works for human reviewers, but automated pipelines need structured, machine-readable data:

- POA&M trackers

- GRC platforms

- SAR documentation

- Continuous monitoring dashboards

The agent’s findings are structured to feed directly into SAR sections, where each control determination needs a status, gap description, and supporting evidence reference. The SDK’s schema validation (covered in the basics section) enforces this: every assessment produces valid, typed JSON.

The schema in src/schemas/grc-schema.ts defines what the agent must return. Here’s the finding-level structure. This is where the federal compliance depth lives:

// Each finding captures FedRAMP-specific fields

control_origination: {

type: "string",

enum: [

"service_provider_corporate",

"service_provider_system",

"customer_responsibility",

"shared",

"inherited",

],

},

inherited_from: { type: "string" },

// e.g., "AWS GovCloud (US) , FedRAMP High P-ATO"

This is a simplified model for the demo; the full FedRAMP SSP template distinguishes seven origination types including hybrid and two customer-specific categories. The five-value enum covers the most common cases.

Control origination is the core concept in cloud authorization. When your system runs on AWS GovCloud, physical security controls are inherited from AWS’s FedRAMP High P-ATO (Provisional Authorization to Operate). Application-level controls are service provider system specific. Some controls are shared: AWS provides the infrastructure, you configure it. In practice, you don’t need the agent to figure this out from scratch. AWS publishes a Customer Compliance Responsibility Matrix (CCRM) that maps every control to its origination. The agent can reference the CCRM and apply the correct designation automatically rather than inferring it. The point here is to show what’s possible with an agent like this, not to prescribe exactly how you should build yours. Some tasks genuinely benefit from agent reasoning; others (like control origination) are a straight lookup. Part of the design work is deciding which is which.

The POA&M entry schema mirrors what a typical Excel POA&M tracker contains:

poam_entry: {

type: "object",

properties: {

weakness_description: { type: "string" },

scheduled_completion_date: { type: "string" },

milestones: { type: "array", items: { /* description, due_date */ } },

source: { type: "string", enum: ["assessment", "scan", "conmon", "incident"] },

status: { type: "string", enum: ["open", "closed", "risk_accepted"] },

deviation_request: { type: "boolean" },

vendor_dependency: { type: "boolean" },

// ... plus point_of_contact, resources_required, original_detection_date

},

},These aren’t arbitrary fields. They reflect typical POA&M tracking requirements you’ll see across federal programs: source tracks whether the finding came from a 3PAO (Third-Party Assessment Organization) assessment, vulnerability scan, continuous monitoring, or incident. deviation_request flags when you’re asking the AO (Authorizing Official) to accept residual risk. vendor_dependency marks findings that require a third-party fix.

At the assessment level, we also capture continuous monitoring metadata:

conmon: {

type: "object",

properties: {

last_full_assessment_date: { type: "string" },

controls_assessed_this_period: { type: "number" },

total_controls_in_baseline: { type: "number" },

annual_assessment_coverage: { type: "number" },

open_scan_findings: { type: "number" },

significant_change_flag: { type: "boolean" },

next_annual_assessment_due: { type: "string" },

},

},Here’s what actual output looks like. This is the IR-4 (Incident Handling) finding from a FedRAMP Moderate assessment. The agent identified two specific gaps: one involving unexercised coordination with US-CERT/CISA (the federal government’s cybersecurity incident reporting channel) documented in the IRP (Incident Response Plan), and another about missing incident tracking tooling. It generated a complete POA&M entry with an ISSO (Information System Security Officer) point of contact:

{

"control_id": "IR-4",

"control_name": "Incident Handling",

"status": "partially_satisfied",

"risk_level": "moderate",

"control_origination": "shared",

"inherited_from": "AWS GovCloud (US) , FedRAMP High P-ATO",

"gap_description": "Two gaps: (1) US-CERT/CISA coordination not exercised. (2) No formal incident tracking system.",

"poam_entry": {

"scheduled_completion_date": "2026-08-02",

"milestones": [

{ "description": "Procure tracking system; schedule coordination exercise", "due_date": "2026-05-04" },

{ "description": "Deploy system and conduct tabletop exercise", "due_date": "2026-08-02" }

],

"source": "assessment",

"status": "open",

"deviation_request": false,

"vendor_dependency": false

}

}

Subagents: delegating specialist work#

We define six specialist subagents, each with a rich purpose description that tells the orchestrator when to delegate:

export const subagents: SubagentConfig[] = [

{

name: "control-assessor",

model: "sonnet",

purpose: "Specialist in control implementation review. Assesses individual controls "

+ "at the enhancement level, determines implementation status and control origination, "

+ "validates evidence sufficiency. Use for detailed control-by-control analysis when "

+ "baselines have 20+ controls or when enhancement-level depth is needed.",

},

{ name: "evidence-reviewer", model: "sonnet", purpose: "Analyzes evidence artifacts for sufficiency, validity, and currency..." },

{ name: "gap-reporter", model: "sonnet", purpose: "Generates detailed gap analysis with remediation guidance and POA&M entries..." },

{ name: "cmmc-specialist", model: "sonnet", purpose: "CMMC-specific assessment logic including level determination..." },

{ name: "ai-governance-specialist", model: "sonnet", purpose: "Specialist in AI governance frameworks: NIST AI RMF, EU AI Act, ISO 42001..." },

{ name: "framework-mapper", model: "haiku", purpose: "Cross-framework control mapping and harmonization analysis..." },

];@dataclass

class SubagentConfig:

name: str

model: str

purpose: str

subagents: list[SubagentConfig] = [

SubagentConfig(

name="control-assessor",

model="sonnet",

purpose=(

"Specialist in control implementation review. Assesses individual controls "

"at the enhancement level, determines implementation status and control origination, "

"validates evidence sufficiency. Use for detailed control-by-control analysis when "

"baselines have 20+ controls or when enhancement-level depth is needed."

),

),

SubagentConfig(name="evidence-reviewer", model="sonnet", purpose="Analyzes evidence artifacts for sufficiency, validity, and currency..."),

SubagentConfig(name="gap-reporter", model="sonnet", purpose="Generates detailed gap analysis with remediation guidance and POA&M entries..."),

SubagentConfig(name="cmmc-specialist", model="sonnet", purpose="CMMC-specific assessment logic including level determination..."),

SubagentConfig(name="ai-governance-specialist", model="sonnet", purpose="Specialist in AI governance frameworks: NIST AI RMF, EU AI Act, ISO 42001..."),

SubagentConfig(name="framework-mapper", model="haiku", purpose="Cross-framework control mapping and harmonization analysis..."),

]These get converted to AgentDefinition objects with enriched prompts and role-specific MCP tools, not just filesystem access. The buildSubagentDefinitions() function assigns each subagent the base tools (Bash, Read, Glob, Grep) plus the MCP tools relevant to its role:

function buildSubagentDefinitions(): Record<string, AgentDefinition> {

return subagents.reduce<Record<string, AgentDefinition>>((acc, agent) => {

const baseTools = ["Bash", "Read", "Glob", "Grep"];

const mcpTools = getSubagentMcpTools(agent.name);

acc[agent.name] = {

description: agent.purpose,

prompt: buildSubagentPrompt(agent),

tools: [...baseTools, ...mcpTools],

model: agent.model,

} as AgentDefinition;

return acc;

}, {});

}def build_subagent_definitions() -> dict[str, AgentDefinition]:

definitions: dict[str, AgentDefinition] = {}

for agent in subagents:

base_tools = ["Bash", "Read", "Glob", "Grep"]

mcp_tools = _get_subagent_mcp_tools(agent.name)

definitions[agent.name] = AgentDefinition(

description=agent.purpose,

prompt=_build_subagent_prompt(agent),

tools=[*base_tools, *mcp_tools],

model=agent.model,

)

return definitionsThe tool mapping gives each subagent exactly what it needs:

- control-assessor:

control_lookup,gap_analyzer,evidence_validator - cmmc-specialist:

control_lookup,cmmc_level_checker,gap_analyzer - framework-mapper:

control_lookup,framework_mapper

No subagent gets the Task tool, so there’s no recursive delegation; execution stays one level deep.

Parallel dispatch#

The main agent (running on Opus) dispatches independent subagent tasks with run_in_background: true via the SDK’s Task tool, then collects results using TaskOutput. For a FedRAMP Moderate assessment, the orchestrator might run these in parallel:

control-assessoranalyzing implementation statusevidence-reviewervalidating artifact sufficiencygap-reportergenerating remediation priorities

The prompt instructs the agent to use this pattern:

- Understand scope: review the framework, baseline, and evidence to determine complexity.

- Delegate specialist work: dispatch subagents with

run_in_background: truefor independent tasks, passing relevant evidence paths. - Collect results: use

TaskOutputto retrieve completed subagent reports. - Synthesize: combine subagent findings into the final JSON assessment.

- Save working notes: write subagent reports to

working/subagent-reports/, evidence analysis toworking/evidence-analysis.md, and the control checklist toworking/control-checklist.md. These persist across turns and are inspectable by human auditors.

Verification patterns#

Verification isn’t just a final step; it happens throughout. The prompt includes a pre-output checklist, and the SDK supports several complementary patterns:

Schema validation: the outputFormat option enforces structure. If the model’s output doesn’t conform to the JSON schema, the SDK retries automatically. This is deterministic: either it matches or it doesn’t.

Bash for composable checks: Bash excels at verification. test -f <path> confirms a file exists. jq '.findings | length' counts findings. grep -c "poam_required.*true" counts POA&M entries. These are fast, deterministic, and composable. The prompt’s verification checklist uses this pattern to confirm control counts match the expected baseline, evidence paths actually exist, POA&M entries are complete for every flagged finding, and remediation timelines align with risk severity (critical ≤30 days, high ≤90, moderate ≤180).

Deterministic vs. semantic verification: some checks are binary (file exists? field present?), others require judgment (is this evidence sufficient?). Use tools and Bash for deterministic checks; reserve model reasoning for semantic validation.

Adversarial subagent review: for high-stakes assessments, you could dispatch a second subagent to review the first’s work. The reviewer doesn’t know the original findings; it re-analyzes the same evidence independently. Discrepancies surface assumptions the first pass made. This isn’t implemented in the demo but is a natural extension of the subagent architecture.

The goal is defense in depth: multiple verification layers, each catching different failure modes. Schema validation catches structural errors. Bash checks catch missing files and counts. Semantic review catches reasoning errors. No single layer is sufficient; together they’re robust.

Orchestration: when to delegate vs. work directly#

Not every assessment needs subagents. The prompt includes decision logic: delegate for complex baselines (20+ controls), CMMC level determinations, AI governance assessments, or when multiple evidence files need cross-referencing. For simple assessments (FedRAMP Low (or FISMA Low) with a single evidence file) the agent works directly, avoiding the overhead of subagent coordination.

This is agent-orchestrated, not code-orchestrated, and the distinction matters. A code-orchestrated approach would require hardcoded thresholds in TypeScript: if (controls.length > 20) dispatch('control-assessor'). That forces you to predict assessment complexity at compile time, using a single dimension (control count) as a proxy for what’s actually a multi-factor decision. The agent-orchestrated approach puts the decision logic in the prompt and lets the model weigh the full context (framework type, baseline size, evidence volume, document quality) to determine whether delegation is worth the coordination overhead. A FedRAMP Moderate assessment with 325 controls but clean, well-organized evidence might not need subagents. A FedRAMP Low/FISMA Low assessment with messy, contradictory evidence might. The routing decision itself requires reasoning, which is exactly what the model is good at.

Why text over JSON for subagent output#

Subagents produce structured text reports (Summary / Findings / Recommendations / Evidence Reviewed sections), not JSON. This is deliberate: enforcing JSON schema output on subagents adds overhead and constrains their ability to provide nuanced analysis. The orchestrator (Opus) handles the harder synthesis step, combining multiple text reports into the final schema-validated JSON. This lets subagents focus on depth of analysis while the orchestrator handles structural compliance.

The framework-mapper uses Haiku since cross-framework mapping is more mechanical; the other specialists use Sonnet for deeper reasoning.

Skills: progressive context disclosure#

The SDK also supports skills, domain knowledge loaded on demand rather than stuffed into the system prompt. A skill is essentially a file (or set of files) that the agent can read when it needs that knowledge.

For GRC, this is a natural fit. An EU AI Act assessment doesn’t need CMMC knowledge in the prompt. A FedRAMP Low assessment doesn’t need IL5 overlay details. Skills let you build a library of framework-specific guidance (control catalogs, parameter tables, assessment procedures) and load only what’s relevant to the current assessment.

The pattern ties into file-system-based context: skills can read working files from previous turns, write intermediate analysis, and build up context progressively. The agent isn’t limited to what fits in the initial prompt; it can pull in knowledge as the assessment unfolds.

Framework data: what the agent knows#

Data lives in data/ as JSON. Here’s what the NIST 800-53 data model looks like for AC-2, notice the enhancement hierarchy and FedRAMP baseline-specific requirements:

{

"id": "AC-2",

"name": "Account Management",

"family": "AC",

"requirements": [

"Define and document account types allowed on the system",

"Assign account managers",

"Establish conditions for group and role membership",

// ... 8 more requirements, one per part (a) through (k)

],

"parts": ["a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g", "h", "i", "j", "k"],

"enhancements": ["AC-2(1)", "AC-2(2)", "AC-2(3)", "AC-2(4)", "AC-2(5)", "AC-2(7)", "..."],

"fedramp_baselines": {

"Low": { "required": true, "enhancements_required": [] },

"Moderate": { "required": true, "enhancements_required": ["AC-2(1)", "AC-2(2)", "AC-2(3)", "AC-2(4)", "AC-2(5)"] },

"High": { "required": true, "enhancements_required": ["AC-2(1)", "AC-2(2)", "AC-2(3)", "AC-2(4)", "AC-2(5)", "AC-2(11)", "AC-2(12)", "AC-2(13)"] }

}

}Each enhancement is also a separate control object with its own requirements and FedRAMP parameter values:

{

"id": "AC-2(3)",

"name": "Disable Accounts",

"parent_control": "AC-2",

"requirements": [

"Disable accounts when the accounts have been inactive for a defined time period"

],

"fedramp_parameters": {

"inactivity_period": "90 days for user accounts"

},

"fedramp_baselines": {

"Low": { "required": false },

"Moderate": { "required": true },

"High": { "required": true }

}

}This is the key: the difference between NIST 800-53 and FedRAMP is the enhancement selection and parameter assignments. FedRAMP takes NIST’s framework and says “for a Moderate system, you MUST implement AC-2(3) and the inactivity period MUST be 90 days.” Our data model captures this explicitly, so the agent knows what to assess at each baseline level.

The baselines file also maps DoD Impact Levels to their FedRAMP requirements. IL4 (CUI) requires a FedRAMP Moderate baseline plus the DISA Cloud Computing SRG IL4 overlay. IL5 (CUI + mission-critical) steps up to FedRAMP High with additional NIST 800-171 requirements. IL6 (classified up to SECRET) adds CNSSI 1253 and ICD 503 overlays. The agent uses these mappings to determine which additional controls apply when a system handles DoD data.

Multi-artifact reasoning: how the agent thinks across evidence#

Here’s where agent-based assessment gets interesting. When we ran AC-2 (Account Management) with just the SSP, the control passed. The narrative described account types, approval authorities, and quarterly reviews. But when we added a placeholder security policy to the evidence set, the agent downgraded AC-2 to partially satisfied:

“Supporting policy is placeholder content and does not substantiate SSP claims.”

The agent treated the empty policy as negative evidence. A policy file that exists but says nothing is worse than no policy at all. It suggests the organization knows a policy is expected but hasn’t written one. This is exactly how a human assessor would reason, and it emerged from the agent’s multi-file analysis without any special logic on our part.

It gets better. When we included an AI system card (biometric identification for critical infrastructure) alongside the NIST 800-53 evidence, the agent flagged it as EU AI Act high-risk, even though we were running a FedRAMP Moderate assessment. The ai_risk_classifier tool picked up the biometric and critical infrastructure keywords, and the agent surfaced that finding unprompted.

With the enhanced SSP (proper FedRAMP structure, part-by-part narratives, control origination), the agent produced enhancement-level findings. Here’s a truncated view of the AC-2 output, notice the control origination and inheritance:

{

"control_id": "AC-2",

"status": "satisfied",

"control_origination": "shared",

"inherited_from": "AWS GovCloud (US) , FedRAMP High P-ATO",

"gap_description": "No material gaps identified. All parts (a) through (k) are addressed.",

"poam_required": false,

"last_assessed_date": "2026-02-03",

"assessment_frequency": "Annual + Continuous Monitoring"

}And each enhancement was assessed individually:

{

"control_id": "AC-2(3)",

"control_name": "Disable Accounts",

"status": "satisfied",

"control_origination": "service_provider_system",

"gap_description": "Inactive accounts auto-disabled after 90 days per FedRAMP parameter."

}This kind of holistic, cross-artifact reasoning is what separates an agentic approach from running GRC checks in isolation. The agent doesn’t just evaluate each control against each file, it builds a picture of the organization’s compliance posture across everything it can see.

High-impact findings (especially those affecting authorization boundaries or inheritable controls) require human review by a qualified assessor before they inform authorization decisions. Cross-framework mappings (e.g., NIST 800-53 to CMMC) are approximate and should be validated against the authoritative source for each framework. The agent accelerates the assessment workflow and catches gaps a manual review might miss, but it doesn’t replace professional judgment.

OSCAL: one path to machine-readable compliance#

Assessment findings tell you what’s wrong. But the SSP itself, the document being assessed, also needs to move toward machine-readable formats if you want automated validation pipelines. OSCAL is one path toward that goal.

We include a sample OSCAL (Open Security Controls Assessment Language) SSP snippet (examples/sample-oscal-ssp.json) that follows the NIST OSCAL schema structure. Here’s what OSCAL looks like for a control implementation, notice the by-components array that captures the shared responsibility model at the data level:

{

"control-id": "ac-2",

"statements": [{

"by-components": [

{ "description": "Service Provider: CloudAI defines account types...", "implementation-status": { "state": "implemented" } },

{ "description": "Inherited from AWS GovCloud: Physical account management...", "implementation-status": { "state": "implemented" } }

]

}]

}FedRAMP 20x is pushing toward machine-readable package management, but it’s worth noting that the program is focused on the outcome (maintaining security packages outside of manual document editing) rather than prescribing a specific format.12 OSCAL happens to be the most mature open standard for structured compliance data, which is why we use it here, but it’s not the only path forward. RFC-0024 defines requirements for machine-readable packages without mandating OSCAL as the format. The agent patterns in this post, scaffold tools that describe a target schema, structured output that constrains the response, agent-driven semantic conversion rather than template filling, are format-agnostic. Swap the OSCAL schema for a platform-native format or a future FedRAMP-specified schema and the same architecture applies.

OSCAL SSP conversion: from Word docs to machine-readable compliance#

The assessment workflow produces findings about an SSP. But there’s a complementary workflow: converting the SSP itself into machine-readable format. As noted above, FedRAMP 20X is moving toward machine-readable authorization packages (though the specific format is still an open question). OSCAL is the most mature schema for this, so that’s what we use here, but the conversion approach (scaffold tool → agent-driven semantic mapping → structured output) works with any target schema. If your SSP lives in a Word doc (most do), converting it to structured data is the first step toward automated ATO workflows.

Agent-driven conversion, not template-filling#

The conversion is agent-driven rather than template-based. A naive approach would regex-match control IDs and paste narratives into a JSON template. The agent approach is better: it semantically understands SSP narratives, distinguishing between service provider implementations and inherited controls, identifying implementation status from context (“planned,” “partially implemented”), and preserving authorization boundary details that matter for FedRAMP assessments.

The agent uses the oscal_ssp_scaffold MCP tool to get the OSCAL SSP structure with required fields and descriptions, then fills it in from the source document. It also calls control_lookup to validate that control IDs in the SSP actually exist in the framework data, catching typos and outdated control references during conversion rather than at submission time.

The pipeline#

flowchart TD

A["Input SSP (.md, .txt, or .docx)"]

B{DOCX?}

C["docling extraction

control metadata + narratives by control part"]

D["Pre-structured conversion prompt"]

E["Agent

(OSCAL SSP JSON schema constraint)"]

F["oscal_ssp_scaffold

for structure"]

G["control_lookup

for validation"]

H["OSCAL SSP JSON output"]

A --> B

B -->|Yes| C

B -->|No| D

C --> D

D --> E

E -.->|uses| F

E -.->|uses| G

F & G --> H

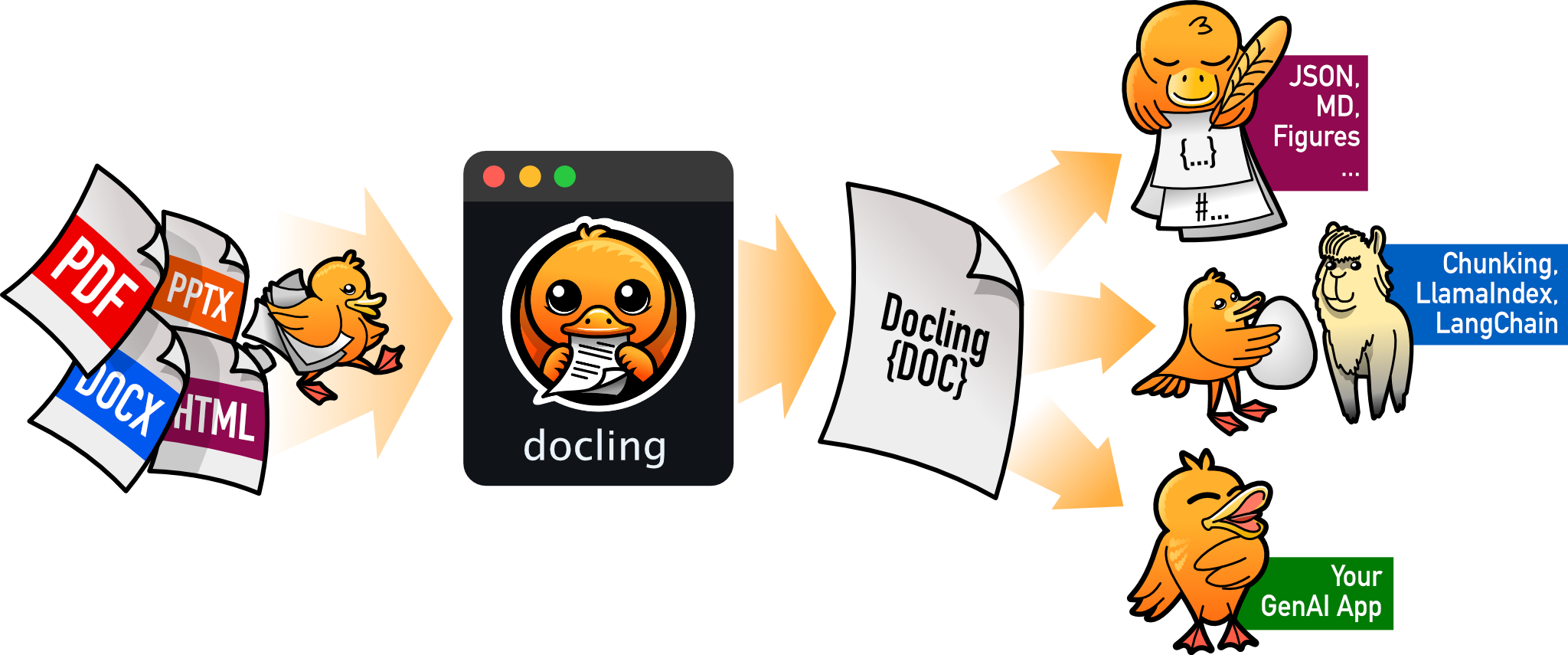

Docling#

docling handles DOCX extraction. It’s one of the best document conversion libraries available right now, especially for structured documents with tables.

The original approach used pandoc to convert DOCX to markdown. For simple SSPs without heavy table structure, that still works, and if you want to see that pattern, the legacy document transformation demo (GitHub) walks through it. But pandoc flattens tables into prose, which falls apart on FedRAMP templates where two structured tables per control carry the metadata you need.

- Pandoc flattens tables into text, losing the two-table-per-control structure

- The agent had to infer control boundaries and parse status checkboxes from prose

- Formatting interpretation burned tokens that should go toward OSCAL mapping

DOCX support now uses docling (pip install docling, v2.54.0+), which preserves table structure. FedRAMP SSP templates use Nx1 single-column tables with inline metadata, two tables per control:

- CIS table: control summary with status, origination, roles, parameters

- Statement table: implementation narratives by control part

Docling parses this programmatically, extracting control IDs, implementation status, origination, and parameters before the agent sees anything. The agent’s job shrinks from “parse a Word doc and convert to OSCAL” to “map these pre-structured narratives to OSCAL fields.”

In practice, structured extraction fits substantially more controls into context than flat-text conversion: the pandoc approach hit limits well before covering a full FedRAMP Moderate baseline, while docling handled it without issue. Let a document parser do document parsing, and let the LLM do semantic mapping.

CLI and REPL usage#

# Direct CLI conversion

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-ssp examples/sample-ssp.md

# Specify output path

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-ssp --output my-ssp.json examples/sample-ssp.md

# DOCX input (requires docling)

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-ssp examples/sample-ssp.docx

# Cross-framework mapping to OSCAL format

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-mapping data/framework-mappings.jsongrc-agent convert --to oscal-ssp ../examples/sample-ssp.md

grc-agent convert --to oscal-ssp --output my-ssp.json ../examples/sample-ssp.md

grc-agent convert --to oscal-mapping ../data/framework-mappings.jsonThe conversion is also available as a REPL command during interactive sessions:

grc> convert oscal-ssp examples/sample-ssp.md

Converting examples/sample-ssp.md to OSCAL SSP format...

OSCAL SSP written to examples/sample-ssp-oscal.jsonStructured output keeps it valid#

The conversion uses the same structured output pattern as the assessment workflow, outputFormat: { type: "json_schema", schema: oscalSspSchema } constrains the agent’s response to valid OSCAL SSP structure. The schema enforces required sections (metadata, system-characteristics, control-implementation) and the implemented-requirements array structure with by-components entries. The agent can’t produce malformed OSCAL because the schema won’t let it.

UUID v5 for deterministic identifiers#

OSCAL supports both UUID v4 (random) and v5 (name-based, SHA-1 hash of namespace + name). We use both, and the distinction matters:

- v4 (random): used for one-off instance identifiers where uniqueness matters more than reproducibility

- v5 (deterministic): used for document-level, component, and control-implementation UUIDs.

uuid5(OSCAL_NAMESPACE, "ac-2")always produces the same identifier

With v4, converting the same SSP twice produces structurally different output, every identifier changes, diffs are useless. With v5, re-running the pipeline gives byte-identical OSCAL where content hasn’t changed. You can diff successive outputs and see exactly which control narratives were updated or which statuses shifted from “planned” to “implemented.”

Both v4 and v5 are first-class RFC-4122 citizens in the OSCAL spec.

Cross-framework mapping in OSCAL format#

OSCAL 1.2.0 introduced a Control Mapping model, a machine-readable way to express relationships between controls across different frameworks. Instead of a flat “AC-2 maps to A.5.15” spreadsheet, OSCAL’s mapping-collection structure captures the nature of the relationship: equivalent-to (same requirement), subset-of (narrower), superset-of (broader), or intersects-with (partial overlap). This is the kind of nuance that matters when organizations need to demonstrate compliance with multiple frameworks simultaneously, knowing that NIST 800-53 AC-2 is equivalent to ISO 27001 A.5.15 means satisfying one automatically satisfies the other.

We already had framework mapping data (data/framework-mappings.json) and a framework_mapper MCP tool for cross-framework lookups. The new convert --to oscal-mapping workflow wraps that data in OSCAL’s mapping-collection structure using the same agent-driven approach, an oscal_mapping_scaffold tool provides the target structure, and the agent infers relationship types from control context. Direct mappings default to equivalent-to; the agent can identify subset/superset relationships when the control scopes clearly differ.

# Cross-framework mapping to OSCAL format

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-mapping data/framework-mappings.json

# Specify output path

npm run start -- convert --to oscal-mapping --output mappings-oscal.json data/framework-mappings.jsongrc-agent convert --to oscal-mapping ../data/framework-mappings.jsonInteractive mode: follow-up questions after assessment#

The single-shot CLI is useful for CI pipelines and automated workflows, but GRC analysts think in conversations: “explain the AC-1 gap,” “what evidence would satisfy AC-2?”, “re-assess if we add this policy.” The --interactive flag enables a REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop, an interactive prompt where you type a question, get an answer, and repeat).

Two-phase architecture#

Interactive mode runs in two phases:

Phase 1 (Assessment): The full runGrcAgent pipeline runs exactly as in single-shot mode, schema-validated structured JSON, same MCP tools, same subagents. You get the same assessment quality.

Phase 2 (Follow-up): A new query() session starts with the assessment result injected as context, but without the outputFormat constraint. This frees the agent to respond in plain text (explaining findings, suggesting evidence, or comparing controls) while still having access to all the same MCP tools.

Why two phases? This isn’t a preference; it’s a hard SDK constraint. The outputFormat option is set once when you create a query() call and cannot be changed mid-session. Every response in that session must conform to the JSON schema. That means follow-up questions like “explain the AC-1 gap” would be forced into schema-shaped JSON instead of readable text. Splitting into two phases gives you strict validation where it matters (the assessment) and natural conversation where it’s useful (follow-ups).

Usage#

npm run start -- --interactive --framework "NIST 800-53" \

--baseline "FedRAMP Moderate" --scope "demo" examples/sample-ssp.mdgrc-agent --interactive --framework "NIST 800-53" \

--baseline "FedRAMP Moderate" --scope "demo" ../examples/sample-ssp.mdAfter the assessment completes, you see a summary and a grc> prompt:

╔══════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ GRC Assessment Complete ║

╚══════════════════════════════════════════╝

Framework: NIST 800-53

Baseline/Level: FedRAMP Moderate

Compliance: 72%

Controls assessed: 14

Controls with gaps: 4

grc> explain the IR-4 gap

The IR-4 (Incident Handling) finding identified two gaps...

grc> what evidence would close AC-2(3)?

To satisfy AC-2(3) (Disable Accounts), you'd need...

grc> json

{ "assessment_metadata": { ... }, "findings": [ ... ] }

grc> exit

Goodbye.Special commands: json dumps the full assessment, exit/quit stops the session.

Session continuity#

Follow-up queries use the SDK’s resume option to maintain conversation context across turns. The first follow-up starts a new session with the assessment injected as context; subsequent follow-ups resume that session so the agent remembers your prior questions and its prior answers. This means you can build on previous exchanges, “now what about AC-3?” works because the agent knows you were just discussing access control gaps.

This also saves tokens. Without resume, every follow-up would need the full assessment JSON re-injected as context, easily 4K+ tokens per turn. With resume, the SDK loads conversation history from the prior session, so you don’t need to re-inject the full assessment JSON on every turn. The agent sees its own prior reasoning naturally, which is both more accurate and more efficient than re-summarizing context.

// First follow-up: inject full assessment context

const prompt = followUpSessionId

? trimmed // subsequent: just the user's question

: `${followUpPrompt}\n\nUser question: ${trimmed}`;

for await (const message of query({

prompt,

options: {

allowedTools: [...GRC_ALLOWED_TOOLS],

mcpServers: { ...GRC_MCP_SERVERS },

maxTurns: 10,

// Resume the follow-up session for conversation continuity

...(followUpSessionId ? { resume: followUpSessionId } : {}),

},

})) { /* stream response */ }# First follow-up: inject full assessment context

prompt_text = (

trimmed if follow_up_session_id

else f"{follow_up_prompt}\n\nUser question: {trimmed}"

)

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

allowed_tools=list(ALLOWED_TOOLS),

mcp_servers=dict(MCP_SERVERS),

max_turns=10,

# Resume the follow-up session for conversation continuity

**({"resume": follow_up_session_id} if follow_up_session_id else {}),

)

async for message in query(prompt=prompt_text, options=options):

# stream responseStreaming responses#

Follow-up responses stream to the terminal in real time via includePartialMessages: true. The REPL extracts content_block_delta events with text_delta payloads (the same streaming protocol the Anthropic API uses) and writes them directly to stdout as they arrive. This gives the analyst immediate feedback rather than waiting for the full response to generate.

Post-assessment utilities#

The repo includes three bash scripts in scripts/ for working with assessment output:

count-controls.sh: summarizes a JSON assessment: findings by status (satisfied/partial/not satisfied), risk level breakdown, POA&M entries required, overall compliance percentage.search-evidence.sh: grep wrapper to search evidence directories by control ID (e.g.,./search-evidence.sh AC-2 evidence/).validate-poam.sh: validates POA&M completeness: checks that required fields (weakness_description,scheduled_completion_date,milestones,source,status) are present for every finding markedpoam_required: true.

These are intentionally simple, the kind of thing you’d write anyway when reviewing assessment output. Having them in the repo means the agent can use them too (via Bash) as part of its verification step.

Hooks: audit trails and compliance logging#

The SDK supports hooks, code that runs before or after tool execution. For GRC, the obvious use case is audit logging: every file read, every tool call, every subagent dispatch gets logged with timestamps and parameters.

This matters for assessment traceability. When an auditor asks “how did you determine IR-4 was partially satisfied?”, you can point to the log: the agent read these evidence files, called gap_analyzer with these parameters, received these results, and made this determination. The assessment isn’t a black box; it’s a traceable sequence of operations.

Hooks can also enforce guardrails: block writes to certain directories, require confirmation for external API calls, or validate tool parameters before execution. For federal environments where data handling is tightly controlled, hooks provide a deterministic layer of policy enforcement that doesn’t depend on the model’s judgment.

Here’s a PreToolUse hook that combines both, an audit logger that also blocks writes to finalized assessment packages. First, the configuration in .claude/settings.json:

{

"hooks": {

"PreToolUse": [

{

"matcher": "Bash",

"hooks": [

{

"type": "command",

"command": "bash .claude/hooks/grc-audit.sh"

}

]

}

]

}

}And the hook script itself:

#!/bin/bash

# .claude/hooks/grc-audit.sh

INPUT=$(cat)

TIMESTAMP=$(date -u +"%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ")

COMMAND=$(echo "$INPUT" | jq -r '.tool_input.command')

# Log every command for assessment traceability

echo "[$TIMESTAMP] $COMMAND" >> .claude/grc-audit.log

# Block modifications to finalized authorization packages

if echo "$COMMAND" | grep -qE '(authorization-packages|final-deliverables)/'; then

echo "Blocked: finalized package directories are read-only during assessment" >&2

exit 2

fi

exit 0Hooks receive the tool input as JSON on stdin. Exit code 0 allows the tool to proceed; exit code 2 blocks it, with stderr fed back to the model as the reason. When an auditor asks how the agent arrived at a finding, the audit log provides a complete, timestamped chain of operations.

Practical use cases#

Beyond this demo, here are high-value applications where GRC teams can get immediate ROI from agents:

FedRAMP readiness reviews. Before submitting a package to a 3PAO, run an agent pipeline that checks your SSP against FedRAMP requirements, validates CIS/CRM mappings, and flags anything a real assessor would catch. This alone can save weeks of back-and-forth.

Continuous monitoring automation. Build an agent that ingests monthly ConMon deliverables (vulnerability scans, configuration baselines, POA&M updates) and generates the monthly report. Wire it to your scanning tools via MCP and let it run on a schedule.

Policy-to-control mapping. Feed organizational policies into an agent and have it map policy statements to NIST 800-53 controls. Especially useful during framework crosswalks (FedRAMP to CMMC, ISO 27001, etc.).

Evidence package assembly. During assessment prep, an agent can crawl a document repo, match evidence artifacts to assessment objectives, and flag missing evidence, turning weeks of evidence collection into hours.

Inheritance analysis. For cloud service providers inheriting controls from IaaS/PaaS providers, an agent can read the provider’s CRM, compare it against your SSP’s inherited control descriptions, and identify discrepancies.

As noted earlier, all examples here use NIST/FedRAMP because those publications are public domain as federal government works. The agent patterns apply to any framework, swap in your own control data and the architecture stays the same.

AI governance: EU AI Act and NIST AI RMF#

The agent assesses AI systems against the EU AI Act, NIST AI RMF, and ISO 42001. When we ran a biometric identification system card against the EU AI Act, the agent assessed 7 articles (Art. 9 Risk Management, Art. 10 Data Governance, Art. 11 Technical Documentation, Art. 13 Transparency, Art. 14 Human Oversight, Art. 15 Accuracy/Robustness, Art. 17 Quality Management) and found 4 critical gaps, going well beyond our starter data through Claude’s own knowledge of the regulation. If you want to browse those articles yourself, they’re all on myctrl.tools.

The ai_rmf_maturity field in the output tracks maturity across the four NIST AI RMF functions:

"ai_rmf_maturity": {

"govern": "ad-hoc",

"map": "ad-hoc",

"measure": "not-started",

"manage": "not-started"

}Where it gets interesting is the federal + AI intersection. We built an example scenario: a DoD AI system (transformer-based NLP) that classifies CUI documents on AWS GovCloud IL5. Run it against CMMC Level 2 and the agent produces 20 findings spanning both traditional security controls (access control, encryption, audit logging) and AI-specific gaps (adversarial robustness, model drift monitoring, ML framework vulnerability tracking). The agent correctly identified that misclassification could route CUI to unauthorized personnel, a compliance risk unique to AI systems in federal environments.

Deploying in Federal and Sovereign Environments#