I’ve been working on adding “agentic” components to some primiative CLI/TUI tools I’ve been brewing lately and it made me question just eaxctly what is an agent really. And I came to the realization that a lot of what’s being called an agent right now out there are just chatbots. An agent actually has to do something for you

The Problem#

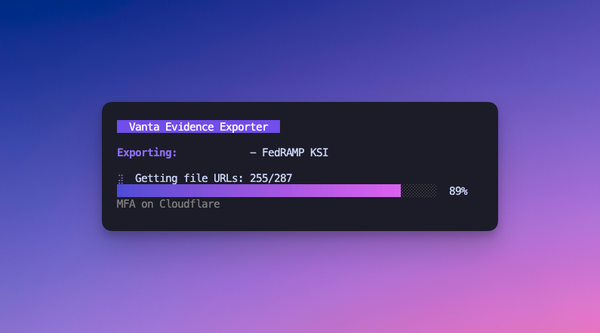

If you’ve ever worked in GRC, you know the drill. An audit is coming up. You need to collect evidence for dozens of controls. That means hunting through file shares, pulling screenshots, exporting logs, and mapping everything back to control requirements. It’s tedious, repetitive, and exactly the kind of work that feels like it should be automated.

I’ve used commercial tools. They’re either expensive, don’t fit our specific workflows, or require more configuration than they’re worth for a PoC. I wanted to see if I could build something useful myself—something that understood our evidence structure and could help navigate it.

What I Learned from Two Great Tutorials#

Before building anything, I read two articles that completely demystified AI agents for me:

Thorsten Ball’s “How to Build an Agent” walks through building a code-editing agent in about 400 lines of Go. His key insight: “An LLM with access to tools, giving it the ability to modify something outside the context window.” That’s it. That’s the whole architecture.

Geoffrey Huntley’s agent workshop reinforces the same pattern: “300 lines of code running in a loop with LLM tokens.” He emphasizes that understanding this pattern transforms you “from being a consumer of AI to a producer of AI who can automate things.”

Both articles converge on the same truth: agents aren’t complex. The magic is in the models, not the code.

The Core Pattern#

Here’s the entire architecture:

graph TD

A[User Input] --> B[Add to Conversation]

B --> C[Send to Claude API]

C --> D{Tool Call?}

D -->|Yes| E[Execute Tool]

E --> F[Add Result to Conversation]

F --> C

D -->|No| G[Display Response]

G --> A

That’s it. You maintain a conversation history, send it to the model, and check if the model wants to call a tool. If it does, you execute the tool locally and send the result back. Then you loop.

In Go, the core loop is about 20 lines:

func main() {

client := anthropic.NewClient()

var conversation []anthropic.Message

for {

// Get user input

input := readUserInput()

conversation = append(conversation, userMessage(input))

// Keep looping until model stops requesting tools

for {

response := client.CreateMessage(conversation, tools)

conversation = append(conversation, response)

// Check if model wants to use a tool

if response.StopReason == "tool_use" {

result := executeTool(response.ToolCall)

conversation = append(conversation, toolResult(result))

continue // Loop back for more inference

}

break // Model is done, wait for next user input

}

}

}The LLM decides when to use tools and how to combine them. You don’t need elaborate orchestration logic or complex state machines. Claude figures out the sequencing on its own.

The Five Tool Primitives#

Both tutorials emphasize that you only need a handful of tools to build something useful. Here’s how I thought about them for GRC.

Each tool is just a struct with a name, description, input schema, and execute function:

type Tool struct {

Name string

Description string

InputSchema json.RawMessage

Execute func(input json.RawMessage) (string, error)

}

var tools = []Tool{

{

Name: "read_file",

Description: "Read contents of a file",

InputSchema: jsonschema.Reflect(&ReadFileInput{}),

Execute: executeReadFile,

},

// ... more tools

}1. Read#

Load file contents into context. In GRC terms: read evidence files, policy documents, framework requirements, or control descriptions. The agent needs to see what it’s working with.

type ReadFileInput struct {

Path string `json:"path" description:"Path to the file to read"`

}

func executeReadFile(input json.RawMessage) (string, error) {

var params ReadFileInput

json.Unmarshal(input, ¶ms)

content, err := os.ReadFile(params.Path)

if err != nil {

return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to read %s: %w", params.Path, err)

}

return string(content), nil

}2. List#

Enumerate files and directories. This lets the agent navigate your evidence folder structure, discover what artifacts exist, and understand the organization of your compliance documentation.

type ListFilesInput struct {

Path string `json:"path" description:"Directory to list"`

}

func executeListFiles(input json.RawMessage) (string, error) {

var params ListFilesInput

json.Unmarshal(input, ¶ms)

var files []string

filepath.Walk(params.Path, func(path string, info os.FileInfo, err error) error {

if info.IsDir() {

files = append(files, path+"/")

} else {

files = append(files, path)

}

return nil

})

result, _ := json.Marshal(files)

return string(result), nil

}3. Search#

Find patterns across files. Think grep, but for controls. The agent can search for specific control IDs, keywords in policies, or evidence references across your entire documentation set.

type SearchInput struct {

Pattern string `json:"pattern" description:"Regex pattern to search for"`

Path string `json:"path" description:"Directory to search in"`

}

func executeSearch(input json.RawMessage) (string, error) {

var params SearchInput

json.Unmarshal(input, ¶ms)

// Shell out to ripgrep for speed

cmd := exec.Command("rg", "--json", params.Pattern, params.Path)

output, err := cmd.Output()

if err != nil {

return "No matches found", nil

}

return string(output), nil

}4. Edit#

Modify files based on what the agent learns. This could mean updating an evidence log, creating a control mapping document, or generating a summary of collected artifacts.

5. Bash#

Execute system commands. Run compliance checks, call APIs, export reports, or interact with other tools in your pipeline. This is the escape hatch for anything the other primitives don’t cover.

How It Works for Evidence Collection#

Here’s what it looks like in practice. You ask the agent to find evidence for a control, and it chains tools together:

Agent receives: "Find evidence for AC-2 Account Management"

→ search(pattern="account|user.provision|access.review", path="./evidence/")

← Returns: ["./evidence/iam/user-provisioning-policy.pdf",

"./evidence/access-reviews/Q4-2024/"]

→ list_files(path="./evidence/access-reviews/Q4-2024/")

← Returns: ["review-2024-10.xlsx", "review-2024-11.xlsx", "review-2024-12.xlsx"]

→ read_file(path="./evidence/iam/user-provisioning-policy.pdf")

← Returns: [policy content...]

Agent responds: "Found 4 artifacts for AC-2. The user provisioning policy

covers account creation workflows. The Q4 access reviews show quarterly

certification of user access. These should satisfy the control requirement."The key insight: you don’t tell the agent how to sequence these calls. It figures out that it needs to search first, then list directories it found, then read specific files. Claude knows how to combine tools without explicit instruction.

Here’s the breakdown of what’s happening:

Receive the control requirement. The agent reads the control description—say, AC-2 (Account Management) from NIST 800-53.

Search for relevant evidence. The agent searches your evidence repository for files matching keywords like “account,” “user provisioning,” “access review,” or specific artifact names you’ve used before.

List available artifacts. Once it finds promising directories, it lists the contents to understand what’s there—screenshots, exports, policies, tickets.

Read and validate. The agent reads the artifacts to confirm they actually satisfy the control requirement. Does this screenshot show what the control asks for? Does this policy cover the required elements?

Organize and map. Finally, the agent can update a tracking document—mapping evidence files to controls, noting gaps, or flagging items that need human review.

The agent handles the navigation and grunt work. You handle the judgment calls.

What It Cost#

- ~$10 in Anthropic API credits. Most of this was spent on iteration—trying different prompts, debugging tool implementations, and experimenting with context management.

- A few hours over a weekend. The core loop is simple. Most time went into thinking about the right tools for GRC workflows and testing with real evidence structures.

Huntley makes a good point about context management: don’t contaminate your context with unrelated information. Keep each session focused on one task. I burned tokens early by being sloppy with this.

Key Takeaways#

You don’t need a SaaS product to experiment. The barrier to building your own agent is surprisingly low. If you can write a basic script and have API access, you can build a useful prototype.

GRC workflows are perfect for this. They’re structured, file-based, and repetitive. Evidence lives in folders. Controls are defined in frameworks. The patterns are predictable enough that an agent can navigate them.

Understanding the pattern changes how you think. Once you see that agents are just loops with tools, you start seeing automation opportunities everywhere. What else is tedious, structured, and file-based in your work?

Start small. A PoC that does one thing well is more useful than a grand vision that never ships. I focused on evidence collection because it’s a pain point I deal with regularly.

Build Your Own#

If this sounds interesting, start with the source material:

- How to Build an Agent - Thorsten Ball’s Go implementation

- Geoffrey Huntley’s Agent Workshop - Broader context and professional relevance

Both are excellent. Pick a workflow that frustrates you, identify the tools you’d need, and start looping. You might be surprised how far $10 and a weekend can take you.